Abstract: Yosef Stepansky

The Ancient Jewish Cemetery in Zefat, Israel: The Epitaphs from the 16th and 17th Centuries and the Problem of their Preservation

Yosef Stepansky, Israel Antiquities Authority

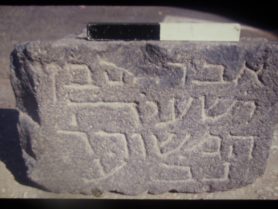

Archaeological epigraphic research in Israel has yielded hundreds of ancient inscriptions, in different scripts and languages. Although much attention has been averted to sensational biblical finds like the 9th c. B.C.E. ‘Beth David’ stele inscription at Tel Dan, the early 10th c. B.C.E. Khirbet Qeiyafa ostracon and – of course – the Dead Sea Scrolls, in fact a large percentage of these inscriptions are ‘day to day’ engraved funerary epitaphs, many of them of Jewish origin albeit written in Greek, Aramaic, Hebrew and other ancient languages. Few of these may still be seen in situ (like at the 2nd-3rd centuries C.E. catacomb burial site at Beit Shearim) while most others – discovered in initiated or in salvage excavations (as in the case of the inscription of ‘Yosef the Son of Eleazar son of Shila of Horsha’ from a 2nd-3rd c. C.E. mausoleum in Tiberias)  or found out of their original context (e.g. the “Avraham ben Yesha’aya the Meshorer’ medieval-period epitaph from Tiberias) – have been taken away to museums, storehouses or private collections.

or found out of their original context (e.g. the “Avraham ben Yesha’aya the Meshorer’ medieval-period epitaph from Tiberias) – have been taken away to museums, storehouses or private collections.

In recent years a large concentration of approximately 50 gravestones bearing Hebrew epitaphs from the 16th and 17th centuries C.E. has been exposed in the ancient cemetery of Zefat, so far the largest group of ancient Hebrew inscriptions that may be observed insitu at one site in Israel. Stylistically, similar epitaphs can be found in the Jewish cemeteries in Istanbul (Kushta) and Salonika, the two largest and most important Jewish centers in the Ottoman Empire. The oldest dated epitaph so far is that of Rabbi Moshe Hadayan, from 1525; we assume that even older ones, from the Mamluke Period (1266-1516 c.e.), are awaiting discovery. Among the gravestones – some with epitaphs that are quite long and composed of riddles and rhymes – are those of the disciples of Rabbi Isaac Luria (“Ha-Ari”) and of Rabbi Yosef Karo, of the heads of Torah Academies in Zefat such as Rabbi Avraham ben Azriel Tarabut (early 16th cent.) and Rabbi Yehoshua Ibn Nun (2nd half of the 16th cent., who was the first to publish the ‘Lurianic’ writings), of well-known women of Zefat (such as Rachel Ha’Ashkenazit Iberlin and Donia Reyna, the sister of Rabbi Chaim Vital), and of other renowned personalities and their siblings (e.g. Rabbi Elazar Azikri composer of the famous liturgical poem ‘Yedid Nefesh’ and his wife Mazal-Tov the granddaughter of Rabbi Yaakov Beirav). From some of the epitaphs we surprisingly learn that a number of Rabbis were also ‘profound (= certified?) physicians’; e.g. Rabbi Yehoshua Ibn Nun and Rabbi Avraham Ibn Ezra (16th c. and not the well-known 12th c. commentator), adding important information on the society of Zefat during that period. Others are of persons whose bones were brought to Israel from abroad, several of which might belong to the Nassi family (relatives of Dona Gracia who herself may have been reburied in Zefat), while others include Rabbi Yosef MiTrani (The ‘Maharit’, son of the ‘Mabit’ of Zefat, who passed away in Turkey and was reburied here in his hometown) and his wife The ‘Rabanit Lady Gracia’ – whose name (‘Gracia’) we learn for the first time. In the cemetery were also found members of the well-known Pinto, Sorogon, De Boton, Elgazi, Sagis, Benveniste, Bahalul and Picchio families, and possible members of the Provencal (southern France) community in 16th c. Zefat who are coined ‘of Narbonne’. Besides the many descendants of these families dispersed throughout the world who for the first time may visit the gravesites of their ancestors buried here in Zefat, their ‘display’ in an open-air – holy site ‘museum’ enables students and tourists to visit the site and to learn first-hand about these personalities who molded the history of Zefat in its golden age – a prime theme in Jewish education with additional economic benefits (tourism).

On the other hand, the uncovering of these epitaphs inscribed on soft-limestone leaves us with an acute problem: their exposure to the elements (some of the inscriptions today even face the sky outright!), after years of being relatively protected by a topsoil-covering, greatly endangers their preservation. In Zefat, with more than 600 mm of rain per year and no protective covering over the gravestones, it’s only a matter of time before most of these ancient gems of epigraphy will wither away. I believe it is urgently imperative to make a sincere effort in protecting the epitaphs from the elements (by covering them, at least from the rain?) and suggest a joint venture with our European counterparts who meet similar challenges pertaining to the thousands of open-air gravestones that are still standing upright in the Jewish cemeteries across Europe.

Bibliography:

Stepansky, Y. and Ben-Tovim, E. 2016. The Ancient Jewish Cemetery in Zefat: Epitaphs from the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century C.E.. In: Grossmark, T. et al. (Eds.), Tel Hai Galilee Studies II (Itai-Bahur Publishing, Zichron Yaakov), pp. 221 – 248 (Hebrew; English Abstract pp. XIX-XX).

Stepansky, Y. 2018. Zefat, 16th and 17th Century CE Epitaphs from the Jewish Cemetery. Israel Genealogy Research Association – Articles: https://genealogy.org.il/articles/

or: https://files7.design-editor.com/90/9007975/UploadedFiles/C575559A-F052-55E5-B5D1-9A494F59657A.pdf (PDF version from the website of Yosef Stepansky: https://www.stepansky.co.il/Publications_and_articles.html)